A new year is a chance to reflect. One highlight for me of 2018 was a workshop I attended in Germany. It took place in Greifswald, the birthplace of Caspar David Friedrich, a 19th century romantic artist. This was a fitting setting to discuss

“Translating the Arts – The Art of Translation”.

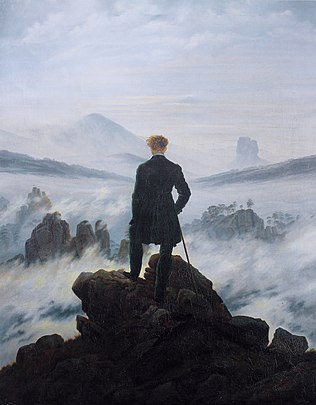

“Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich

(image taken from wikimedia commons)

The light in Friedrich’s works gives an air of magic. Landscapes dominate and people are in the shadows or depicted as a “Rückenfigur” (with their back to the viewer). A translator is similarly in the shadows, but reveals the landscape of a text to the reader in a different light.

Translators play a crucial role in the creative arts and literature. Here, style is important, not just content. “It’s not what you say, but the way that you say it.” In German, this becomes “Der Ton macht die Musik”, literally “The sound makes the music.” Sometimes, this can lead to odd expressions. For example, something was gained in translation when “break a leg” came to mean “good luck”, as the original phrase was misheard. Being familiar with proverbs and sayings is important. Otherwise, a literal translation would not make sense.

The magic of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books has been translated into 70 languages. Invented words, riddles and anagrams create great challenges to a translator. Tom Marvolo Riddle is Harry’s nemesis Voldemort. His name is an anagram of “I am Lord Voldemort”. On translation, his moniker has to change:

Tom Vorlost Riddle (German) = ist Lord Voldemort

[is Lord Voldemort]

Tom Elvis Jedusor (French) = Je suis Voldemort

[I am Voldemort]

Marten Asmodom Vilijn (Dutch) = Mijn naam is Voldemort

[My name is Voldemort]

Tom Gus Mervolo Dolder (Swedish) = ego sum Lord Voldemort

[I am Lord Voldemort] Here, the translator opted for Latin rather than Swedish.

Tom Dredolo Venster (Norwegian) = Voldemort den store

[Voldemort the great]

Without subtitles, film and TV fans might miss out on great drama and comedy from around the world. Good subtitles seamlessly express dialogue whilst allowing time to enjoy the images. Subtitlers have to compromise though, as a maximum of two lines appears on screen. Sometimes, text is shortened; a passive phrase becomes active; an indirect question, direct; a double negative becomes positive; or the viewer is simply provided with the sense of the dialogue. There is a stark contrast between accuracy and the art of a translation. The viewer wants to understand not just what characters are saying, but subtle nuances, which also reveal their emotions.

Mozart’s “The Magic Flute”, an instant success in late 18th century Vienna, only became popular in the 20th century in the UK when translated by Edward Dent, then Professor of Music at Cambridge. Translating opera for performance means the music has to come first. The libretto (the words) must be singable, make sense, be natural and respect the rhythm and rhyme of the original. Some translations are “Textbuch” (textbook) while others are “Textbruch” (they take liberties).

From Wagner’s use in “Siegfried” of modal incongruence, where words or actions contrast with the music, to neologisms such as “Wunschmaid” (“wish-maiden” or “wish-daughter”), the translator faces many challenges, most recently tackled by Jeremy Sams’ 2005 translation. Alfred Kalisch’s 1912 translation of Richard Strauss’ “Rosenkavalier” is still the most frequently used. Hofmannstal’s invented language, known as “Sprachkostüm”; formal and colloquial Austrian dialogue; and a mix of tragedy and farce feature here. An example captures the rhythm of the original:

“Heut oder morgen oder den übernächsten Tag” (literally, “Today or tomorrow or the day after tomorrow”) is translated as “Now or to-morrow: if not to-morrow, very soon.”

In these examples, the translator remains hidden. A successful translation flows effortlessly and the audience feels at home as if the words being viewed or heard were original and not re-conveyed. Jeremy Sams perhaps makes the best conclusion: “Translation is an interesting paradox. Sometimes things have to radically change in order to seem the same.”

With thanks to Jadwiga Bobrowska and Stephanie Tarling of the Chartered Institute of Linguists’ German Society for organising this weekend workshop in June 2018 along with Professor Harry Walter of Greifswald University (proverbs); translator Nick Tanner (Harry Potter); subtitler Andrea Kirchhartz (subtitling); and translator and poet Sandy Jones (libretti).

Nice insights, Alison. It was a pleasure to read this article.

As a father of two kids, I often listen to nursery rhymes with them, and it is astonishing to hear some of the choices made by translators when songs are translated from English to Portuguese.

A song that’s nice and pleasant to the ears is often translated, and simply translated, rather than adapted or transcreated. The result? Something that doesn’t rhyme at all. The meaning is preserved, but the impact on the listener is awful. The song is no longer pleasant to listen to. A nursery rhyme… that doesn’t rhyme.

That is something terrible. They forget that, in a song, rhymes are more important than the exact meaning, otherwise it will no longer be a song, but just a bunch of words together.

Fortunately there are exceptions and some people with some good judgement out there 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind comments Matheus. Yes, it’s very true that the sound of nursery rhymes in particular is very important. At least, there are some good translations of songs, as you say.

LikeLike